by Hozan Alan Senauke

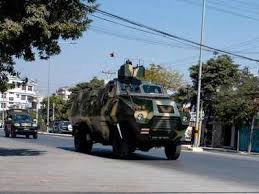

On February 1, 2021, the day before a new Myanmar parliament was to be sworn in following an election in November, the majority civilian government was ousted by the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military. With tanks and armored cars rolling through the streets of Yangon and other cities, the military declared a one-year “state of emergency.” Full leadership was claimed by General Min Aung Hlaing, Commander-in-Chief of Defense Services. In early morning raids, State Councilor Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint, along with numerous ministers, deputies, members of parliament, and known activists were swept up and taken to jails or to house arrest.

Soldiers stand guard on a street in Naypyidaw on February 1, 2021, after the military detained the country’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi and the country’s president in a coup. (Photo by STR / AFP)

While this coup surprised most of the world, its rumbling approach could be felt in the few months since November’s national election. The Tatmadaw, which directly or indirectly has controlled the government and economy of Myanmar (also known as Burma) for nearly sixty years, saw a vast majority of parliamentary seats—396 of a total of 476 seats—assigned to Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD). Only 33 seats were won by the military’s proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party. According to the 2008 constitution, the Tatmadaw itself is given the power to appoint 25% of the parliament, but the results of last November’s election would have given the NLD a super-majority, which might have enabled them constitutionally to break the iron grip of the military.

Myanmar’s election took place on November 8, two days after the United States election. It is chilling to hear similar allegations of “election fraud,” offered by General Min Aung Hlaing and other leading generals. It is very likely that the generals were paying close attention to Donald Trump’s unproven incitements about voting irregularities. Reverting to a rhetoric of Orwellian doublespeak, Min Aung Hlaing said:

The constitution is the mother law for all laws. So we all need to abide by the constitution. If one does not follow the law, such law must be revoked. If it is the constitution, it is necessary to revoke the constitution.

On Wednesday, Min Aung Hlaing told senior officers that the constitution could be revoked if the laws are not being properly enforced. According to Reuters:

Diplomatic missions in Myanmar also issued a joint statement on Friday expressing support for the democratic process. “We urge the military, and all other parties in the country, to adhere to democratic norms, and we oppose any attempt to alter the outcome of the elections or impede Myanmar’s democratic transition,” said the statement issued by the EU, the U.S., Australia and others.

In the coup’s immediate aftermath, television and internet were blocked, financial institutions closed, and troops were visible in the cities. Two days later, some of these services have been restored, but there’s tension and fear in the streets. According to the BBC:

…car horns and the banging of cooking pots could be heard in the streets of Yangon in a sign of protest. A campaign of civil disobedience appeared to be gathering steam with doctors working in government hospitals saying they would stop work from Wednesday to push for Ms Suu Kyi’s release.

Activists hold a portrait of Myanmar’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi during a protest outside the United Nations University building in Tokyo on February 1, 2021. (Photo by Philip FONG / AFP)

Aung San Suu Kyi has herself not been seen since she was placed in house arrest by the military on Monday at her villa in Myanmar’s artificially constructed capital, Naypidaw. A statement in her name—but lacking her signature—was released by NLD representatives.

The actions of the military are actions to put the country back under a dictatorship…I urge people not to accept this, to respond and wholeheartedly to protest against the coup by the military.

Then on February 4 came this unlikely twist—as reported by the New York Times:

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the Myanmar civilian leader deposed by the military in a coup, was charged on Wednesday with an obscure infraction: having illegally imported at least 10 walkie-talkies, according to an official from her National League for Democracy party. The violation can be punishable by up to three years in prison.

It was a bizarre postscript to a fraught 48 hours in which the army placed the country’s most popular leader back under house arrest and extinguished hopes that the Southeast Asian nation could one day serve as a beacon of democracy in a world awash with rising authoritarianism.

But Myanmar or Burma has never been a beacon of democracy. Violence has inevitably been the mark of regime change there. Burma gained independence from British India in January of 1948. Only a few months earlier, eight members of the pre-independence interim government of the Union of Burma were machine-gunned during a cabinet meeting. Among the dead was General Aung San, father of Aung San Suu Kyi, who was just a child when he was assassinated.

In 1962, with a Communist insurrection on the borders and protests and instability across the country, General Ne Win took control in a military coup, imposing a brutal and irrational dictatorship. His “Burmese Way to Socialism” led the nation into an economic tailspin that took it from agricultural self-sufficiency to grinding poverty in less than a generation.

In 1988, facing economic unrest and resistance to longstanding political oppression, students and monks led a democratic uprising that coincided with Aung San Suu Kyi’s return to the country from Great Britain. This movement was again met with violence and the displacement of aging Ne Win with a junta of Tatmadaw generals, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC—one of those acronyms out of a James Bond movie). Several years later SLORC was renamed the less pronounceable SPDC— the State Peace and Development Council—but it was the same old junta.

With SPDC imposition of radical price increases in fuel, rice, cooking oil and other basic commodities in 2007, the country, renamed Myanmar by the junta, faced another round of peaceful protests, led by large numbers of Burmese monks and nuns, who were joined by activists, and other citizens. The Saffron Revolution, named for the color of the monks’ robes, faced an extremely violent reaction from the Tatmadaw. Deaths and disappearances at the hands of the military are still undetermined, but the fabric of society was badly torn. From my own experience in Myanmar, just a month later in December 2007, clouds of fear covered the country.

Less than a year later, in May of 2008, Cyclone Nargis, the most destructive storm in Myanmar’s history, devastated the highly populated Irrawaddy Delta, leaving several hundred thousand people dead, and more than a million people homeless. Relief efforts, tightly controlled by SPDC, were disorganized and inadequate. International aid agencies were prevented from delivering needed supplies, with rescue vessels from the West and all the Asian nation anchored helplessly offshore.

In a sense, this appeared to be the SPDC’s last gasp of mismanagement and insensitivity. The other shoe had dropped. A new constitution was passed by referendum in 2008 and the country’s name was changed to the “Republic of the Union of Myanmar.” General elections were held under the new constitution in 2010, with substantial electoral gains for the previously banned National League for Democracy. But in their campaigns for legitimacy based on the window-dressing of democracy, the generals have consistently over-estimated their own popularity and under-estimated the grassroots longing for actual democracy. In each election since 1990, flawed as the electoral process may have been, the generals have lost big and have back-pedaled to insure military rule. Clearly this pattern cannot persist forever, but many thousands have paid the price in human rights, imprisonment, and death in opposition to a regime that seems impervious to anything but military force or economic pressure.

The coup is also a desperate move by General Min Aung Hlaing, whose term as senior general was due to expire later this year. In power since 2011, he has been an engineer of the military’s murderous campaign again the Rohingya, driving 1,000,000 desperately poor people out of Myanmar, mostly to vast camps of stateless, displaced people in nearby Bangladesh.

Min Aung Hlaing, who is relatively young at 55, is known to have presidential ambitions, which were thwarted by the NLD landslide in November. This coup is his extra-legal attempt to extend his military seniority until the end of the emergency, likely to last at least two years. We should also be prepared to witness constitutional manipulations which will land him in the presidency.

As for Aung San Suu Kyi, her status as an icon of democratic values has been badly tainted while serving as Myanmar’s State Councilor since 2016, often supporting military backers in their genocidal attack on the Muslim Rohingya, armed oppression of Kachin, Shan, and other minority peoples, and their suppression of press and democratic rights.

As the daughter of Aung San, founder of Burma’s army, it seems she had an ungrounded belief that the Tatmadaw could be an agent of change and democratization.

Meanwhile many of the international accolades and honorary positions granted to Aung San Suu Kyi have been publicly rescinded. At the same time, her NLD party’s huge electoral victory in November testifies to her enduring popularity at home. So, her very presence remains a threat to military hegemony. We must defend Aung San Suu Kyi as Myanmar’s chosen leader, while remaining critical of the Burmese chauvinism that has given the Tatmadaw a free hand to impose brutal power over the ethnic minorities.

***

Recent photo in Myanmar from Al Jazeera.

At this point, as the implications of Myanmar’s coup continue to unfold, we in the United States support the Biden administration and the U.S. State Department’s review of potential sanctions against the government of Myanmar, and particularly against the generals, who are major stakeholders in branches of multinational corporations in Myanmar. Targeted sanctions against individual members of the junta would be a first priority.

Along with that, we can apply pressure on these corporations, which include Kirin Brewing, Toshiba, H&M apparel, L.L. Bean and other large businesses. Boycotts can be organized by human rights organizations. The Biden administration has the ability to coordinate with our allies—relieved to see the close of the Trump era—to new sanctions and embargoes. See the Action Network link here and below for letter-writing and lobbying campaigns. We hope that friends and allies across the world will join forces in these campaigns.

We should demand that Facebook remove military accounts and all pages advocating violence from their network. While Facebook presently reaches more than half of Myanmar’s population of 53 million, its track record on human rights has been deplorable over the last five years, allowing provocation and images of violence to flourish on its platform. This week, Facebook banned a Myanmar military network page following the coup. A leaked internal document designates the country as a “temporary high-risk location,” and promises to employ “a number of product interventions that were used in the past…to ensure the platform isn’t being used to spread misinformation, incite violence, or coordinate harm.” Meanwhile, on February 4, the junta has, at least temporarily, blocked Facebook in Myanmar through February 7.

According to the United Nations press office on Thursday, February 4:

The UN Security Council issued a press statement…expressing “deep concern” over the military takeover in Myanmar, calling for the immediate release if the country’s elected leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and President Win Myint.

Security Council members “emphasized the need for continued support of the democratic transition.”

Thursday’s statement calls for the “immediate release of all those detained,” and stresses “the need to uphold democratic institutions and processes, refrain from violence, and fully respect human rights, fundamental freedoms and the rule of law.”

We also urge the United Nations to take actions, including enforcing the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which outlaws international arms transfers used to inflict human rights violations on citizens and populations—which in Myanmar would include the overthrow of a constitutionally-elected government, and sustained warfare against Myanmar’s ethnic minorities. As of 2019, the top seven nations providing arms to Myanmar include China, North Korea, India, Israel, the Philippines, Russia, and Ukraine. Fourteen companies from these nations have been supplying fighter jets, missiles, armored vehicles, and warships to Myanmar’s military.

***

The other shoe has dropped, and we do not know which path the people and government of Myanmar are going to follow. How will the citizenry respond? Will the Tatmadaw see the democratic handwriting on the wall, stepping back gracefully or going down fighting? For many of us in Buddhist traditions, at this moment we wonder where are the monastics, Burma’s monks and nuns, who have often been agents of change and justice at historical junctures.

Admittedly, after their heroic role in the Saffron Revolution, many of Myanmar’s monks, particularly leadership and members of the outlawed Ma Ba Tha, the Committee to Protect Race and Religion, showed themselves in alignment with a kind of Buddhist nationalism. These monks, in league with the military, and with the assent of Aung San Suu Kyi, fanned flames of violence against the Rohingya and other Muslims inside the country. As we wrote in an international appeal for peace and sanity in 2017: “We are greatly disturbed by what many see as slander and distortion of the Buddha’s teachings. In the Dhamma there is no justification for hatred and violence.”

Still, today as then, I deeply trust that the Buddha’s teachings of peace and equality will finally lead Myanmar and in fact, all of us, to a land of liberation.

RESOURCES & CONTACTS

Petitions and Calls to Action from the International Campaign for the Rohingya

1 Comment

Pia · February 7, 2021 at 12:42 am

dear Hozan,

general Min Aung Hlaing is actually 64. they increased the age of mandatory retirement from 60 to 65 to accommodate him.

Comments are closed.